Zip The “What Is It?”

One curious little fellow from New Jersey enjoyed a long and fruitful career as one of P.T. Barnum’s star attractions. Billed as “Zip The What Is It?,” he was gazed upon by millions of people and touted as the survivor of a lost tribe discovered in the Amazon during the exploration of the River Gamba. The truth is that Zip was born William Henry Johnson in rural Liberty Corners, NJ.

Circus freaks have always been looked upon as somewhat “show business impaired” in regards to the glitter and glamorous lifestyles shared by those performers of normal stature. But one curious little fellow from New Jersey enjoyed a long and fruitful career as one of P.T. Barnum’s star attractions. Billed as “Zip The What Is It?,” he was gazed upon by millions of people and touted as the survivor of a lost tribe discovered in the Amazon during the exploration of the River Gamba.

The truth is that Zip was born William Henry Johnson in rural Liberty Corner, NJ. He was the son of William and Mahalia Johnson, former slaves, and one of six siblings. Zip was a bit different from birth–his body developed, but his head was very small, and it was believed his brain never functioned properly. He was described as “having the head like the slim end of an egg, a long broad nose and a prognathous jaw.” Although in later years he displayed as much common sense as anyone else, the tiny head is what attracted agents from the nearby Van Emburgh’s Circus in Somerville to Zip’s door. The circus folk were tipped off by the Johnsons’ neighbors who would frequent the traveling sideshows. They suggested someone take a look at the little-noggined Zip.

The truth is that Zip was born William Henry Johnson in rural Liberty Corner, NJ. He was the son of William and Mahalia Johnson, former slaves, and one of six siblings. Zip was a bit different from birth–his body developed, but his head was very small, and it was believed his brain never functioned properly. He was described as “having the head like the slim end of an egg, a long broad nose and a prognathous jaw.” Although in later years he displayed as much common sense as anyone else, the tiny head is what attracted agents from the nearby Van Emburgh’s Circus in Somerville to Zip’s door. The circus folk were tipped off by the Johnsons’ neighbors who would frequent the traveling sideshows. They suggested someone take a look at the little-noggined Zip.

After striking an agreement with Zip’s parents, who saw the opportunity to make some money, Van Emburgh added Zip to its sideshow exhibit. He instantly became the talk of the circus. Zip’s agent, seeing the success the boy was having, decided to show him to master showman P.T. Barnum, in hopes of selling him to the world’s greatest collector of human oddities. When Barnum first saw Zip, he told the agent of a similar fellow he had shown to Charles Dickens the previous year. When Dickens asked, “What is it?” Barnum thought that would be a perfect name for his newly found “feral human.” Barnum’s original “What Is It” turned out to be an English actor by the name of Harvey Leech, a white man with deformed legs who delighted audiences in New York as a What is It? character for a short time before being exposed as a fraud. There also may have been a third actor who portrayed the What is It?, or William Johnson may have started performing years earlier than records show.

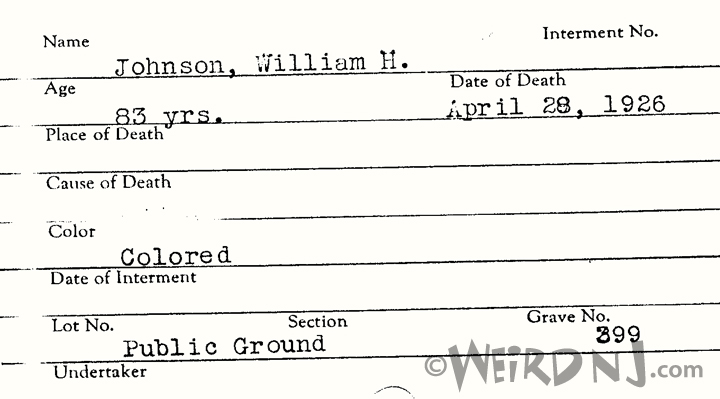

While Johnson’s tombstone dates him at age 69 upon his death, his death certificate lists his at age 83. This has led to ambivalence about whether Johnson was the second or third person to assume the mantle of the What Is It? Regardless of who was portraying the character, Barnum knew a good name when he heard it. And when he saw Zip he was convinced that he’d found the ultimate “What Is It?” and came to a reasonable agreement to take Zip on.

While Johnson’s tombstone dates him at age 69 upon his death, his death certificate lists his at age 83. This has led to ambivalence about whether Johnson was the second or third person to assume the mantle of the What Is It? Regardless of who was portraying the character, Barnum knew a good name when he heard it. And when he saw Zip he was convinced that he’d found the ultimate “What Is It?” and came to a reasonable agreement to take Zip on.

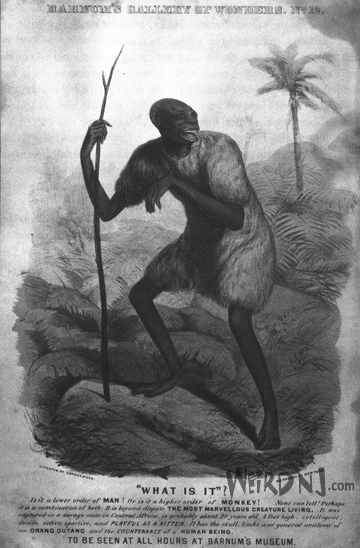

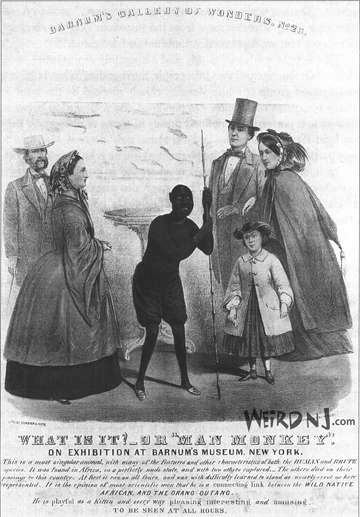

Barnum gave Zip a makeover, shaving his cranium, except for a little tuft of shaggy hair on the back of his head. Knowing the fervor the nation was gripped with due to the recent publication of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species, Barnum fitted Zip with a furry monkey outfit, which became the most famous prop in Zip’s identity. Barnum promoted Zip as a “nondescript”-lying somewhere in the realm between monkey and man. At certain points in his career, he was even billed as being from a land “beyond the Moon.”

Barnum’s infamous ability to promote strange exhibits was at its most potent when dealing with Zip. “When he first came,” the program of one Zip appearance read, “his only food was raw meat, sweet apples, oranges, and nuts, all of which he was very fond; but he will now eat bread, cake, and similar things, though he is fonder of raw meat.” As author James W. Cook writes in his book The Arts of Deception, “Barnum offered What Is It? as a newly discovered quasi-man, born a ‘brute’ in the African jungle, but beginning to take on various human features during his stay in New York.”

Barnum’s infamous ability to promote strange exhibits was at its most potent when dealing with Zip. “When he first came,” the program of one Zip appearance read, “his only food was raw meat, sweet apples, oranges, and nuts, all of which he was very fond; but he will now eat bread, cake, and similar things, though he is fonder of raw meat.” As author James W. Cook writes in his book The Arts of Deception, “Barnum offered What Is It? as a newly discovered quasi-man, born a ‘brute’ in the African jungle, but beginning to take on various human features during his stay in New York.”

“The American people love to be humbugged,” Barnum was fond of saying, and his audience certainly did love Zip. He gave Zip an extra dollar every day he would remain silent, piquing the curiosity of all that viewed him. While on exhibition, Zip would speak an undecipherable dialect. Zip’s sister, Mrs. Sarah Van Duyne, claimed in a 1926 interview that her brother would “converse like the average person, and with fair reasoning power,” when he came to visit her.

Zip was not a true “pinhead”, or “microcephalous,” but his conical head and small face made him the prize of the circus sideshows. He stood proudly amongst his friends; Jim Carver, the Texas Giant, Major Mite, the Smallest Man in the World, the Ambassadors from Mars, and other performing human oddities. Pictures of Zip appeared in all the major newspapers. Matthew Brady, the famed Civil War photographer even had tintypes of Zip made, and proclaimed him the “Dean Of The Freaks.” Zip performed for audiences all over the United States for over 67 years.

In an excerpt from M.H. Werner’s book Barnum, appears the following:

“On October 13, 1860, the Prince Of Wales, later King Edward VII, visited Barnum’s American Museum. With great interest, Albert Edward examined the Siamese Twins and What Is It? According to the New York Herald, the latter was a deformed idiotic negro boy, whom Barnum exhibited as the connecting link between man and ape. The advertising sheets used during these years by Barnum always listed among the freaks ‘What Is It? or Man Monkey.’”

Zip drew a good salary from Barnum, and when P.T. joined forces with America’s other circus dynasty, Ringling Brothers, Zip went along with the package. Much of his career was spent working for the world-famous sideshow of the Ringling Brothers and even earning himself the central place of honor on his own platform alongside the other best-known sideshow performers of the day. He was very proud of that honor, and kept a popgun under his chair to ward off anyone that would try to usurp his throne.

circus dynasty, Ringling Brothers, Zip went along with the package. Much of his career was spent working for the world-famous sideshow of the Ringling Brothers and even earning himself the central place of honor on his own platform alongside the other best-known sideshow performers of the day. He was very proud of that honor, and kept a popgun under his chair to ward off anyone that would try to usurp his throne.

During the famous trial of John Scopes, the Tennesseean schoolteacher who dared to teach Darwin’s theory of evolution, Zip offered himself as evidence, and was ready to take the stand as a “missing link.” Always the consummate showman, that Zip.

Zip also performed with a fiddle for the audience as part of his repertoire. Although he did not know how to play the instrument, the audience could not get enough of Zip dancing and squeaking his fiddle. He first got the idea to play the violin from Cliquot, the African Bushman who played a ukulele. Zip noticed that people would crowd around Cliquot whenever he’d strum the instrument, and that made Zip jealous. A large crowd meant Cliquot could sell photographs of himself for 10¢ apiece.

Zip also performed with a fiddle for the audience as part of his repertoire. Although he did not know how to play the instrument, the audience could not get enough of Zip dancing and squeaking his fiddle. He first got the idea to play the violin from Cliquot, the African Bushman who played a ukulele. Zip noticed that people would crowd around Cliquot whenever he’d strum the instrument, and that made Zip jealous. A large crowd meant Cliquot could sell photographs of himself for 10¢ apiece.

One day when the circus was passing through Zainesville, Ohio, Zip bought a fiddle that was rumored to be the instrument that Daniel Boone fiddled on when he would get lost in the wilds of Kentucky. Zip began playing it immediately, and almost instantly started making money. Maybe Zip wasn’t the feeble-minded idiot he pretended to be after all. Soon, people offered to pay Zip to not play his beloved fiddle. Even the performers would pay him daily to keep silent. It was estimated that for the six years he played the violin, it netted him almost $14,000.

Captain O.K. White, Zip’s manager for over 25 years, gave Zip a tuxedo, which he kept for the rest of his life, occasionally breaking it out for birthdays and special events. It was rumored that Zip had amassed a small fortune over the course of his long showbiz career. Captain White invested some of Zip’s money and did very well, even investing in a chicken farm in Nutley, NJ.

Captain O.K. White, Zip’s manager for over 25 years, gave Zip a tuxedo, which he kept for the rest of his life, occasionally breaking it out for birthdays and special events. It was rumored that Zip had amassed a small fortune over the course of his long showbiz career. Captain White invested some of Zip’s money and did very well, even investing in a chicken farm in Nutley, NJ.

In his eighties, Zip still performed at the Coney Island Freak Show, being easy to travel to from his Bound Brook, NJ home. One Sunday afternoon in 1925, during one of his strolls on the boardwalk, Zip heard a little girl cry out for help. He noticed the girl waving her arms in the ocean and swam out to rescue her. He instantly became a hero, being cheered by all those who had witnessed the event, but Zip shyly ran away from the attention of being a good Samaritan.

Despite his advanced age, Zip was always ready at a moment’s notice to play the “Missing Link.” His physical vigor was said to be remarkable, and at 80 years old he had yet to lose a tooth.

Zip was taken seriously ill three weeks before his death with bronchitis and influenza. He was performing in the circus scene of the musical comedy “Sunny” at the New Amsterdam Theater. Although against the wishes of his doctor and Captain White, he finished the production before settling at his home in Bound Brook. He was moved from Bound Brook to Bellevue Hospital in New York, when pneumonia developed. With his sister at the side of his deathbed, Zip uttered his now famous dying words: “Well,” he said, “we fooled ’em for a long time.” Zip died on April 9, 1926.

Zip was laid out in his beloved black tuxedo. The funeral home that day was filled to capacity with his fellow freak performers, paying their last respects to the greatest freak of them all. Among the mourners were Jim Tarver, the Texas Giant, Jack Earle, the Tallest Man in the World, and Jolly Irene, a morosely obese woman who needed a whole pew to herself just to sit down. Other celebrity mourners were not so easily identifiable. Frank Graf, The Tattooed Man, wore a modest suit. Joe Kramer, the man with the rubber neck, stood in the rear with Alphonso, The Human Ostrich, who had known Zip for many years. Other friends of Zip – Gus Birchman, The Human Claw Hammer and Ajax the Sword Swallower, sat silently in the crowd.

The funeral was brief and simple. The soloist sang “Going Home” as Zip’s freaky friends walked before his casket to say their last goodbyes. Zip’s mortal remains were interred in the Bound Brook Cemetery on April 26, 1926.

It was estimated that during his life, Zip was viewed by more than 100 million people. He became the “Oldest Living Freak,” and was adored by kings and countries. Few people that walk by his grave today, which is marked by a simple stone bearing the inscription “William H. Johnson 1857-1926,” would realize that it was the final resting place of a man who was a legend in his own time––a little noggined fellow who led a life larger than most.

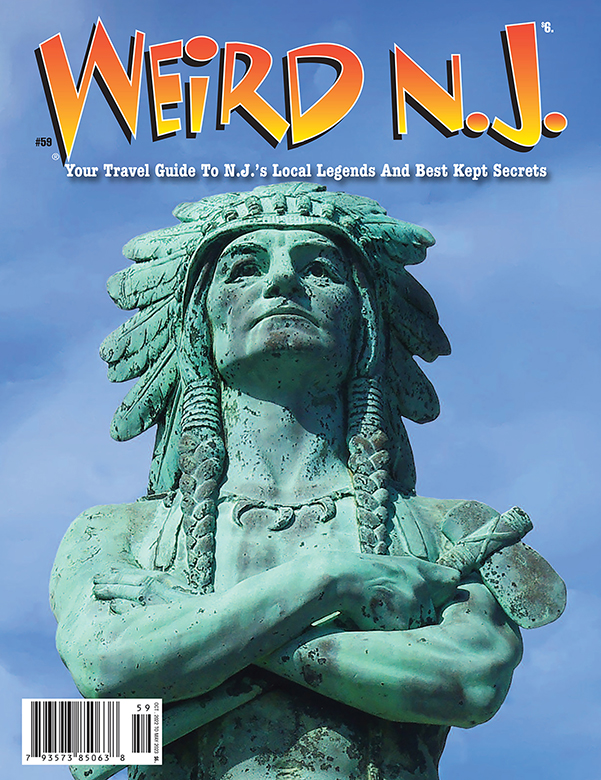

The preceding article is an excerpt from Weird NJ magazine, “Your Travel Guide to New Jersey’s Local Legends and Best Kept Secrets,” which is available on newsstands throughout the state and on the web at www.WeirdNJ.com. All contents ©Weird NJ and may not be reproduced by any means without permission.

Visit our SHOP for all of your Weird NJ needs: Magazines, Books, Posters, Shirts, Patches, Stickers, Magnets, Air Fresheners. Show the world your Jersey pride some of our Jersey-centric goodies!

Now you can have all of your favorite Weird NJ icons on all kinds of cool new Weird Wear, Men’s Wear, Women’s Wear, Kids, Tee Shirts, Sweatshirts, Long Sleeve Tees, Hoodies, Tanks Tops, Hats, Mugs & Backpacks! All are available in all sizes and a variety of colors. Visit WEIRD NJ MERCH CENTRAL. Represent New Jersey!

![]()