Obituary for NJ’s Own “5th Beatle” Andy White

We just received the sad news that Andy White, the Scottish studio session musician who played the drums on Love Me Do and other early tracks by The Beatles, died here in his adopted home of New Jersey. According to his family, the 85-year-old died on Monday following a stroke. White was chosen ahead of Ringo Starr in September 1962 to play drums on the single version of Love Me Do and its B-side, P.S. I Love You. White, who was born in Glasgow in 1930, is also believed to have played on the album version of Please Please Me.

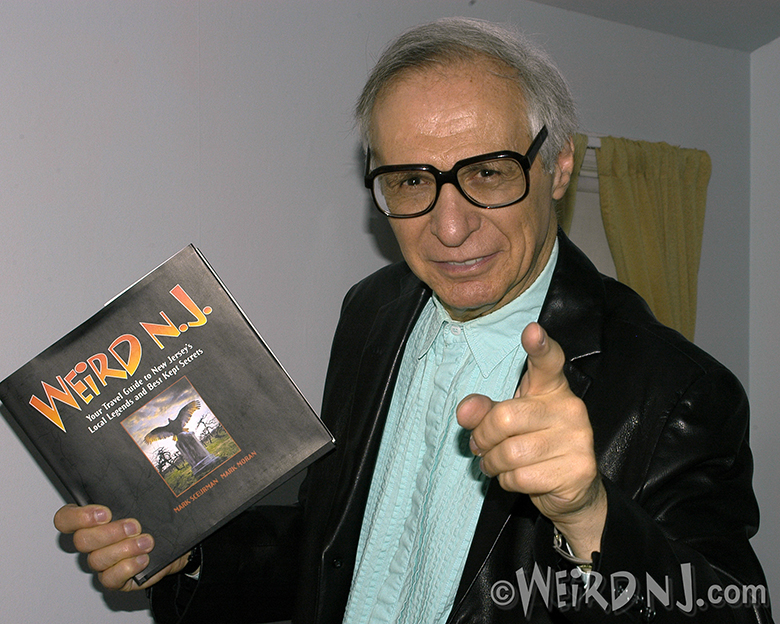

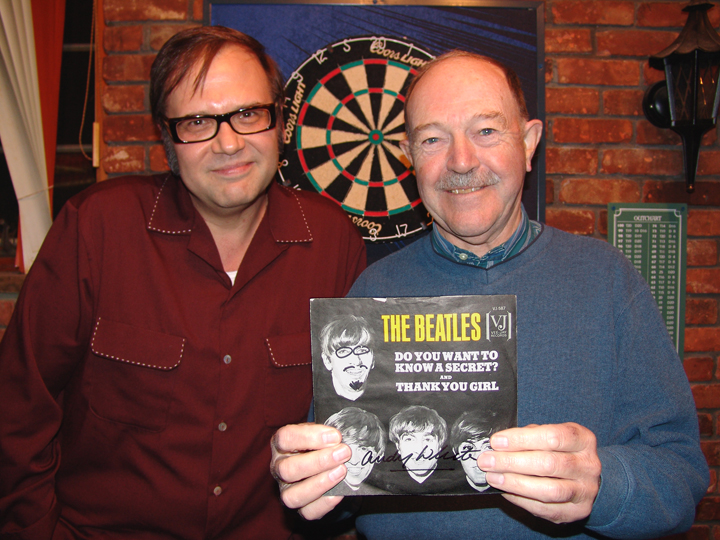

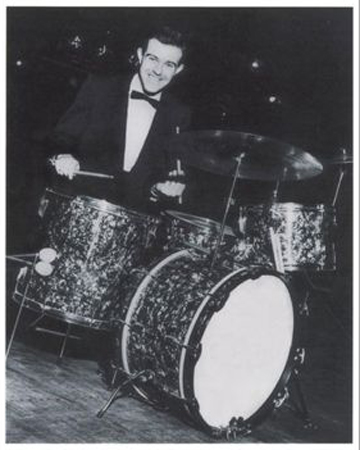

Weird NJ, along with Smithereens’ drummer Dennis Diken, had the great pleasure of sitting down with Mr. White for an interview a few years back in West Orange, NJ where he taught drums for many years. In the following story Andy tells the story of that fateful day back in 1962 when he played a part in changing the future of music forever.

Meet the (Fifth) Beatle, Right Here in New Jersey

There are a few people who have been referred to as the “Fifth Beatle” in the history of music’s greatest hit making combo: George Martin and Brian Epstein, the group’s producer and manager respectively, Pete Best, their original drummer, and Billy Preston who occasionally play keyboards with the group, to name just a few. There is one New Jersey resident who is also among this small cadre who can lay a legitimate claim to the title––Andy White. Andy was a session drummer who was called in to play on some of the Beatles’ earliest studio recordings, along side all the other official Fab Four members. In the following interview another legendary New Jersey drummer, Dennis Diken (of The Smithereens and Dennis Diken with Bell Sound fame) sits down to speak with Mr. White about his curious part in Rock ‘n’ Roll history, and about how he came all the way from Abbey Road to Weird NJ.

By Dennis Diken

One of the greatest epiphanies of my life occurred when I discovered that some members of my favorite musical groups didn’t play on all of their own records. As it were, I’d already figured out that there wasn’t any Santa Claus at a very young age, and somehow that was cool. It didn’t particularly bum me out or shatter my childhood. Oddly, it was more confounding to learn that session great Hal Blaine drummed on The Beach Boys’ “California Girls.”

For the record, the bands’ regular stickmeister Dennis Wilson proved to be a good player onstage with the Boys and can be heard on a bunch of their seminal sides and cuts throughout the group’s career. And indeed, a heap of the discs that gave us kids of the ‘60s a new way of walking and talking were created by talented teenaged self-contained units. But while many young Rock ‘n’ Roll combos could wail with an exciting live show, some may not have possessed the chops to cut a solid track under the microscopic scrutiny of the recording studio. At least, not to the satisfaction of producers who expected to have two or three songs in the can within a three-hour session. Time was money and seasoned studio musicians had the ability and finesse to conjure just the magic groove on demand and supply the “hit sound” that spelled big sales.

Here’s another thing that eventually dawned on me and messed with my inquiring mind. These men and women were clocking, on the average, 12-18 hour days, cutting pop, jazz, soundtracks, TV themes, and jingles. The framework of a classic disc that may have had a life-changing wallop on us and our culture was not necessarily beamed down from the cosmos. In fact, it was the product of folks “going to work.” They didn’t have the time to wait around for inspiration to hit. They were just doing their job!

Because these masters did their thing in the shadow of the stars after stars after stars they backed, session musicians typically are a talkative lot who, given the chance, like to seek credit where credit is due. A guy like Hal Blaine, who is very probably the most recorded musician in history, boasts an unequalled discography that speaks for itself. He’s drummed on monster hits by Sinatra, Presley, Streisand, The Beach Boys, Simon & Garfunkel, The Mamas & The Papas, The Carpenters and the biggest chunk of Phil Spector’s wall of sound. Then there are some others (who shall go nameless) that laughably maintain they ghosted for others, including one Jersey guy who affirms that he beat tubs on 21 Beatles tracks (titles yet to be disclosed, after nearly 40 years) and that “Ringo didn’t play on nothing.” While this is a load of rubbish, there is another chap who resides in the Garden State who rightfully lives up to his custom license plate, which reads 5THBEATLE. His name is Andy White.

In October of 1962, The Beatles released “Love Me Do” (backed with “PS I Love You”), their first single for the British EMI subsidiary Parlophone and thus launched their amazing career. They had recorded the song three times. The first stab featured the group’s original thumper Pete Best (available on The Beatles Anthology 1) and a superior remake was later attempted with “new guy” Ringo Starr. But when the fabulous four reported to London’s Abbey Road studio to wax said tune again, they found that producer George Martin had hired a certain Mr. White to keep the beat that day, leaving Ringo to shake maracas and tambourine instead. Martin had been nonplussed by the drumming of Best and presumably Starr didn’t float his boat at that time either. Andy knew the ropes of studio playing and could be counted on to deliver the goods.

In October of 1962, The Beatles released “Love Me Do” (backed with “PS I Love You”), their first single for the British EMI subsidiary Parlophone and thus launched their amazing career. They had recorded the song three times. The first stab featured the group’s original thumper Pete Best (available on The Beatles Anthology 1) and a superior remake was later attempted with “new guy” Ringo Starr. But when the fabulous four reported to London’s Abbey Road studio to wax said tune again, they found that producer George Martin had hired a certain Mr. White to keep the beat that day, leaving Ringo to shake maracas and tambourine instead. Martin had been nonplussed by the drumming of Best and presumably Starr didn’t float his boat at that time either. Andy knew the ropes of studio playing and could be counted on to deliver the goods.

Ringo recounted that day in the studio in The Beatles Anthology (Chronicle Books, 2000): “On my first visit (to EMI) in September we just ran through some tracks for George Martin. We even did ‘Please Pleased Me’. I remember that, because while we were recording it I was playing the bass drum with a maraca in one hand and a tambourine in the other. I think it’s because of that that George Martin used Andy White, the ‘professional’. When we went down a week later to record ‘Love Me Do’. The guy was previously booked, anyway, because of Pete Best. George didn’t want to take any more chances and I was caught in the middle.

“I was devastated that George Martin had his doubts about me. I came down ready to roll and heard, ‘We’ve got a professional drummer.’ … So Andy plays on the ‘Love Me Do’ single – but I play later on the album version; Andy wasn’t doing anything so great that I couldn’t copy it when we did the album.”

Oddly enough, it was Ringo’s laid back version of “Love Me Do” that found its way (allegedly by mistake) to the initial pressings of the British 45 (later changed) while White’s “big-beat” take is the version that appeared on the Please Please Me album and the US single (on the Tollie label) that we Yanks know and love. And indeed, Ringo drums away solidly and tastefully on the other 12 (out of 14) tracks of that maiden Beatles long-player. By summer ’63, his confidence was clearly intact as he debuted his trademark extroverted swing and verve on “She Loves You.”

Yet, poor Starr must have been crestfallen and left to ponder his future with his musical mates as he stood in that lonely corner of Abbey Road, playing second tambourine to White on that fateful September day in 1962. Was this Ringo’s epiphany? Do we have Andy to thank for inadvertently inspiring Starr to rise to heights that would kick the butts of his fellow Liverpudlians and ultimately please George Martin?

The aforementioned license plate happens to be tagged onto a vehicle registered in New Jersey. Andy White, former star of London studios now teaches students of marching drums in the Garden State. It was a gas to finally meet and speak with the mythical figure who lurked in the shadows of Beatles lore for decades. I joined weird NJ’s Mark Moran and Mark Sceurman, along with our pal Chris Bolger one fine autumn night at the Shillelagh Club in West Orange where we shared a few pints of Guinness with one of the finest drummers to come out of Great Britain. Unlike many other behind-the-sceners, Andy was unnecessarily humble and soft-spoken. He had forgotten more than we’ll ever know about the history of the UK pop music scene and we did our best to pry information out of him. Unfortunately (for us), British session musicians received cash pay packets at the end of each studio date so no union contracts were filed. As a result, we have no written record of who played on what. ‘Tis a shame.

But this we do know. Andy was born in Glasgow, Scotland and started playing the drums when he was 12, in a pipe band formed by his Boy Scout troop. He didn’t listen to a lot of music as a kid, though he cites John Phillip Sousa as an early influence. “In the elementary school we were in they used to march us in from the playground, and they played records of Sousa marches. Even today when I hear a Sousa march I have to go out and march around!” Through fellow pipe band musicians, he was turned on to the modern jazz sounds of “Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, and Bebop and all” and he dug drummers Max Roach, Art Blakey, and Buddy Rich. He formed a combo and played “a form of jazz, if you will,” but they were just learning at that point.

He Moved from Glasgow to London in the early fifties and began his playing career, working strictly as a musician.

Dennis Diken: How did you finally make the transition from live touring drummer to studio player?

Andy White: Well, there were many steps on the way. I left the touring band and tried a jazz group in London. It was only for maybe a year, but there again it was in all these jazz clubs in London.

Mark Moran: Were you familiar with Rock ‘n’ Roll? Did it have any appeal for you, being from a jazz and traditional background?

AW: Oh, no, I didn’t mind it at all. Well, because, you know, it’s rhythm and blues…

MM: I know, a gig is a gig, right? But, were you attracted to it all?

AW: No, it swung its own way, you know. But the point was, we played in this Rock ‘n’ Roll show and we only did three numbers. The top of the bill was Bill Haley and the Comets. And the Buddy Johnson band backed all the acts. We only did these three numbers, but they gave me firsthand a taste of Rock ‘n’ Roll at the top of the scale.

DD: And you toured the states?

AW: Well, we were only in the states for three weeks. But we did quite a bit of the East Coast, and we got our first taste of the south.

MM: Was this your first trip to America?

AW: Yes, yes it was.

MM: What’d you think of it?

AW: Oh, I loved it.

MM: Did you visit New Jersey on that tour?

AW: No, no we didn’t do New Jersey.

DD: What were some of the early hits you played on? Does anything stick out in your mind?

AW: Well round about that same time, was Tom Jones’ “It’s Not Unusual.”

DD: You played on that one?

AW: Yeah, yeah.

MM: That’s a good one!

Mark Sceurman: So whenever you hear that song, what do you think of?

AW: Oh, that’s great. That’s a great record.

MM: Was Tom Jones there when you recorded that? Or did you lay down the tracks without him?

AW: Oh yeah. He sang it. He was there.

DD: A big production. Well, the Beatles session would have predated that, I believe. Because I think “It’s Not Unusual” was ’64 or ’65. And “Love Me Do” was before that. Had you done a lot of work with George Martin prior to that?

AW: No, no. In fact, George Martin doesn’t like session musicians. He said they got too much money!

MM: How much money did you get for that session?

AW: I think it was like 21 dollars. Oh yeah, and 10 shillings porterage for transporting your drums, you know.

DD: So George Martin thought that was too much money, huh? And that was a good wage in that day, right.

AW: Oh, yeah, it was good. It was a lot of money.

MM: So had you heard of the Beatles before you got called in to do the session?

AW: Well, I did, because my first wife was a singer. Lynn Cornell. She was in the Vernons Girls.

MM: But, the Beatles hadn’t made a record before “Love Me Do,” so how did you know about them?

AW: Well, because she came from Liverpool. So she knew all about the Beatles, ahead of them.

DD: So you recorded “Love Me Do” and “PS I Love You” in the same session? Those two songs?

AW: And a version of “Please Please Me,” which I believe was on the first album they did. My version.

DD: Is that right? Really!?

MS: You can tell?

AW: Oh, I can tell, yeah! (laughter)

DD: Did he know when Ringo showed up for the session that you were going to be doing the drums on the track? Did he know in advance?

AW: I don’t think so, because he always talks about coming into the studio and seeing somebody else setting up drums, and he thought, ‘Uh oh! This is another Pete Best situation!’

DD: Yeah, right, cause he was so new to the group at that time, I’m sure his confidence was shaken.

AW: Right, sure. He still talks about it.

MM: Was it ever explained to you why you were there drumming for a group that had already been playing for quite some time? I mean, did anybody say to you, ‘This is why you’re here…’

AW: No, no. I didn’t even know who I was gonna play with. I just knew, ‘Show up at this time.’

MM: Well, that’s gotta be an uncomfortable situation. I mean, here comes four guys that were in a band, you’re there sitting on drums, their drummer is in the room…nobody explained to you?

AW: But I didn’t know that he was a drummer, you know.

MS: So, did you have to learn the song, or they just said, ‘Here’s the beat, do it’?

AW: Well, the thing is they’d already been playing those songs for some time, so they had their routine. And most of my time was learning the routine, you know, for each song. And then, once it was reasonable, they put the red light on.

DD: So you had to do a couple of run-throughs. Probably didn’t take long.

AW: Yeah, because “Love Me Do” wasn’t too bad. And then, “PS I Love You,” it just continues like a chapter. We did “Please Please Me” also. That took longer because that’s a little more complex.

DD: People don’t talk about that record. Although, your version was not the original single version. Is that correct, in England? They put Ringo’s version out.

AW: In Britain it came out as a single.

DD: The first version was Ringo’s, though.

AW: I’m not sure about that, you know.

DD: I’m pretty sure. Because it was reissued a couple of years ago as a commemorative thing, an anniversary thing, and they made a point in all the press to say that Ringo’s version was the original Parlophone single. Not in America – the one we grew up with was Andy’s version. And the one on the album is Andy’s version. But you can clearly hear the difference.

MM: Yeah, but why would they have released Ringo’s version in England first when they hired Andy to make that record?

DD: It’s a good question. It’s an interesting question. Why would they release it at all, for that matter?

AW: And if you listen to the drums, the sound is entirely different.

MS: Your version is clearly superior, right? (laughter) So Andy, would you consider yourself the sixth, seventh, or eighth Beatle? (laughter)

AW: I’ve got a ‘five’ sticker on the car so I’ll go with that. (laughter)

DD: When did you move to America?

AW: In ’83.

MM: So what got you here to New Jersey?

AW: Well, my second wife came from Caldwell.

MM: So what do you think of New Jersey?

AW: I like it! I think I’ll stay! (laughter)

DD: So, how long have you been doing what you’re doing here, like what you’re teaching tonight?

AW: Quite a long time, yeah. Because I have had that as my roots. I’ve still dabbled or even played in pipe bands all during that period, all of my life.

DD: That’s your first musical love, isn’t it?

AW: Yeah, and I knew many of the big names in pipe bands.

MM: But you’ve got a real place in history. People can’t talk about the origins of the Beatles without your name coming up…just for that one little session you did. What did you think when the Beatles went on to become so successful? You had no idea at the time where they would go. What did you think as they skyrocketed?

AW: I thought it was great. The music we did in that session was absolutely original. And it was their music. And it was different. I liked the music, I thought it had great potential.

DD: They never called you back for another session, did they? Did they have any contact with you after that at all?

AW: No, no. The only person I spoke to was Paul, once. And I just happened to be doing a session in EMI and he was there, nothing to do with me. Just ran into him. He did say hello!

MM: Did you get along with him during the session? Everything went well?

AW: Oh yeah, yeah. Well, I was only really involved with him and John during the session, not George. He was there, but they were giving me the routine.

MS: Did they fool around, have fun, or were they just straight, you know?

AW: They didn’t have time!

MM: Yeah, once that red light goes on––I mean they’d record an entire album in sixteen hours!

DD: I’d be curious again if you could ever remember any other beat groups that you ghosted for, you know. You never worked for Herman’s Hermits, or…

AW: Well I did, I did a couple.

DD: Do you remember titles?

AW: I think one of them was “Henry the Eighth.”

DD: Oh, that’s really cool. That’s got that tight beat to it.

AW: Yeah, that “Boy Meets Girl” thing (A ‘60s-era British T.V. show), you had Eddie Cochran. That’s when he was killed. He was on his way back, he was coming home from the airport in London and smash, car crash. What a player he was.

DD: Yeah, he was great, wasn’t he? Did you play with Jerry and the Pacemakers? The Animals?

AW: No, no. I think a lot of them did their own, self-contained.

MM: Well, that’s what I think is the funny thing about this – the whole interest in you playing on the Beatles’ first record. When we were kids we just assumed that those bands were playing all their own records.

AW: Oh, sure.

DD: Why wouldn’t we?

MM: And that all got exploded with the Monkees and then everybody just assumed nobody was playing their own instruments, and then when you find out that the Beatles had a session drummer, it just blew people’s minds.

DD: I mean, that was like next to there being no Santa!

MM: Yeah, it was. That’s exactly it! It’s the Easter Bunny en masse. And maybe that’s why Ringo’s so…got it stuck in his craw. They were one of the bands who, aside from that session, who always did, always were a unit, a band. Which was relatively unheard of.

DD: They were the first.

MM: So, did you get credited on those records as session artist?

AW: No, no. They never credited me on any records. Unless it’s like big band or something.

MS: But evidently, years later, you’re finally getting your reward. I mean you are being credited for doing this.

AW: It’s too late now, though! (laughter) I’m not getting residuals!

DD: Do you know if you played on any other Tom Jones hits?

AW: Well, funnily enough, I think I subbed for another drummer on “What’s New, Pussycat?”

DD: Oh yeah, was that you?

AW: Yeah, it was done for a movie…and they used that cut.

MM: That’s a great one. You’ve been playing on and been to so many amazing sessions. Were there any sessions that you came out of and thought, ‘This song, these songs that we recorded today, are going to be earth shattering! They’re going to be monster hits.’

AW: No, no.

MM: Never! You never got the vibe that there was something incredible that you were just a part of?

AW: No, you just…you liked it or you didn’t.

DD: But, did you have a sense that it was more than just a job to you? Were you happy to be creating, rather than just punching a clock, so to speak?

AW: No, no of course. If it was good, you recognized it, sure. There were good ones, but there were a lot of run of the mill.

DD: Do you ever hear something on the radio and go, ‘Hey, that was me!’

AW: I just did it the other day! I was in a local supermarket, and they played “Love Me Do.” And I stopped!

MM: When you hear that, how long does it take before you can figure out which version it is? If it’s yours?

AW: Two bars.

DD: You never hear Ringo’s version. It’s very rare that you hear that.

MM: He’d argue with you on that!

AW: The main thing is the sound of the drums.

DD: Ringo was playing very lightly on his version, very swingy. Andy just comes right on the downbeat. Did you do any session work in America?

AW: No, no.

DD: None at all? Would you like to?

AW: Oh, sure! (laughter)

MM: So you’d like it to be known when people read this interview that you are available for all session work!

AW: Sitting by the phone, yes! But we’d have to negotiate a good rate! (laughter) I’m getting sick of humping drums around!

For more information about Dennis Diken’s many musical projects please visit www.DennisDiken.com.