Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital

Longtime Weird NJ contributor Phillip Buehler is about to release a book he has written and taken photographs for entitled WOODY GUTHRIE’S WARDY FORTY: Greystone Park State Hospital Revisited. Phil has just established a Kickstarter page to raise fund for the printing of this amazing documentation.

Greystone Becomes “Gravestone”

Currently the State plans to demolish the historic main building at the closed Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital. Officials recently made the decision after receiving six “expressions of interest” from groups interested in redeveloping the 678,000-square-foot Kirkbride Building on the hospital’s campus in Parsippany. It was built in 1876 and closed in 2008. The tentative plan is to start the demolition work in February or March of 2014.

Longtime Weird NJ contributor Phillip Buehler is about to release a book he has written and taken photographs for entitled WOODY GUTHRIE’S WARDY FORTY: Greystone Park State Hospital Revisited. Phil has just established a Kickstarter page to raise fund for the printing of this amazing documentation. According to Phil, “The reason for the Kickstarter is that we wanted to print a high quality book here in the U.S. (like Woody would have wanted) and don’t want to price the book at $150 a copy since printing here is many times more than printing in China.”

http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/614091395/woody-guthries-wardy-forty-greystone-hospital-revi

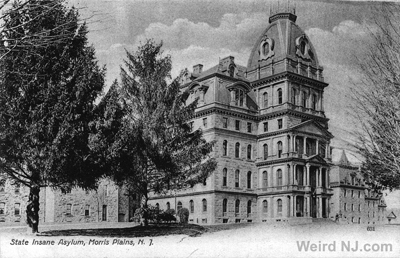

One of the more infamous asylums in New Jersey lore is Greystone, located in Morris Plains/Parsippany. First conceived in1871 and known as The New Jersey State Lunatic Asylum at Morristown, the institution first opened its doors (to a mere 292 patients) on August 17, 1876.

In its day, Greystone was a landmark in progressivism. Designed by Thomas Kirkbride, the hospital advocated uncrowded conditions, fresh air, and the notion that mental patients were curable people. Over time, the humane reputation of Greystone was tarnished, as overcrowding became the norm (the hospital, which was originally meant to house hundreds, once contained 7,674 patients in1953). Overcrowding was a problem almost immediately in the hospital’s history. In 1881 the attic was converted into patient living space, and in 1887, the hospital’s exercise rooms were converted into more dormitories.

In its day, Greystone was a landmark in progressivism. Designed by Thomas Kirkbride, the hospital advocated uncrowded conditions, fresh air, and the notion that mental patients were curable people. Over time, the humane reputation of Greystone was tarnished, as overcrowding became the norm (the hospital, which was originally meant to house hundreds, once contained 7,674 patients in1953). Overcrowding was a problem almost immediately in the hospital’s history. In 1881 the attic was converted into patient living space, and in 1887, the hospital’s exercise rooms were converted into more dormitories.

One of the hospitals more famous patients was folk singer/songwriter Woody Guthrie, who spend a stint at Greystone from 1956 to 1961. Woody was suffering from Huntington’s disease, a hereditary, degenerative nervous disorder which would eventual prove terminal. During his stay there, Woody referred to Greystone as “Gravestone.” This sardonically humorous nickname might prove more prophetic than Woody ever could have imagined, as Greystone might well be the last monument to a dying breed of New Jersey’s gargantuan mental institutions.

Many of the building at Greystone went abandoned long ago. The hospital was recently ordered closed altogether due to sexual abuses by employees against patients, patient on patient violence, and multiple patient suicides. Though historical societies have expressed a desire to preserve the older buildings of Greystone, the fate of the grand old asylum is still up in the air at the time of this writing. Sadly, the time of these massive abandoned behemoth asylums may soon come to an end. But the experience of exploring them in their abandoned state is still indelibly etched in the memories of those who once ventured inside.

The Weird NJ interview Phillip Buehler

For the past ten year artist Phillip Buehler has been exploring the ruins of Greystone Park Insane Asylum in Morris Plains, NJ and doing extensive research of the Woody Guthrie Archives. Woody Guthrie, the legendary folksinger, songwriter, and political activist was committed to Greystone on May 29, 1956, after he was arrested for “wandering aimlessly on the highways.” He spent the rest of his life in psychiatric hospitals and died in 1967 of Huntington’s disease, an incurable degenerative disease that he inherited from his mother.

Buehler has just completed a book based on his investigations of Woody Guthrie’s life and Greystone’s history. He calls the it “Wardy Forty,” which was Woody’s nickname for his hospital ward at Greystone, which he referred to as “Gravestone.” The book seeks to bring to light a forgotten piece of American history – the commitment of a cultural icon to a state mental institution – and to simultaneously make us reflect on how Greystone’s abandonment and decay is connected to how we ignore, isolate, or forget the embarrassing, unpleasant, or traumatic.

Buehler has just completed a book based on his investigations of Woody Guthrie’s life and Greystone’s history. He calls the it “Wardy Forty,” which was Woody’s nickname for his hospital ward at Greystone, which he referred to as “Gravestone.” The book seeks to bring to light a forgotten piece of American history – the commitment of a cultural icon to a state mental institution – and to simultaneously make us reflect on how Greystone’s abandonment and decay is connected to how we ignore, isolate, or forget the embarrassing, unpleasant, or traumatic.

Greystone Park was spread over 1,000 acres and had 8,500 patients while Guthrie was there. The main building was constructed in 1877 and had the largest foundation of any building in the United States until the Pentagon was completed in the 1940s. Greystone, like many other state hospitals, was notorious for patient neglect and abuse. Most of Greystone Park was abandoned in the 1970s with the advent of new drugs and changing attitudes about warehousing the mentally ill. As the state of New Jersey has recently decided to dispose of the property at Greystone Park, the buildings will most likely be destroyed in the next few years.

Buehler spent many days at the Woody Guthrie Archives searching through hundreds of letters and medical papers. Support from the Guthrie family led to the release of material that has never before been made public, including letters, home movies, and photographs of Guthrie and his family at Greystone.

WNJ: When did your fascination with ruins begin?

I grew up in New Jersey, the first real post-modern state. I started photographing ruins 35 years ago in high school, when a friend and I decided to explore Ellis Island. At the time it was totally abandoned, so we headed out in a 12-foot aluminum rowboat. We went back a few times to take photographs and make a 16mm film abut the island, always staying away from the windows on the side facing Liberty Island where park rangers were. I’ve since photographed dozens of ruins, many of which I have put up on my website at modern-ruins.com. I always look to bring to the surface some lost piece of history or memory that is still relevant today.

Why did you first go to Greystone?

It was a summer weekend and I was looking for another adventure, so I called Mark Moran for a lead on someplace to shoot. Mark suggested Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital. So I asked a friend, Bill Graef, who is also and artist, if he’d like to come on a photo safari, and off we went.

What was your first trip like?

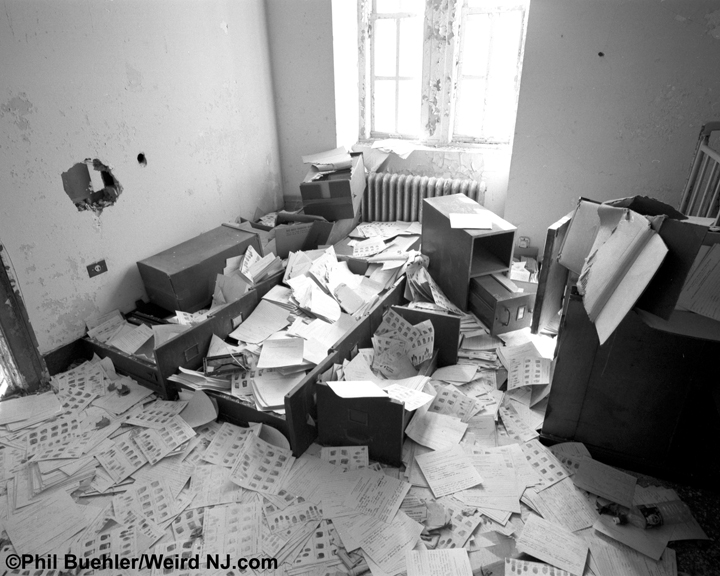

Greystone Park is a huge institution, with many buildings on 1,000 acres. Some of the buildings are still in use as there are still around 400 patients there. There weren’t any “no trespassing” signs around so we went up to one of the abandoned buildings and walked right in an open door. It’s since been sealed up pretty tight. Almost immediately we came across the remnants of the darkroom and patient mugshot files – none had names, just case numbers and dates. Going through a bunch it seemed like most patients were there for around three months, with a photo taken when they were admitted and another when they were discharged.

At its peak Greystone had around 10,000 patients, so there were a lot of mugshots. Looking through some of them from the 50s and 60s, it looked like the patients were way more interesting and alive when they arrived than when they were discharged. One guy looked like James Dean in one photo and a postal worker with a tie in the other. A woman looked very sexy with long hair and seemed to have been turned into a domesticated, conforming housewife. It looked like the last thing Greystone did before releasing a patient was to give them a haircut.

From forms scattered around you could see the place had been abandoned since the mid-1970s. We spent the day wandering around the abandoned wards. While mostly empty, there were still traces of life there, from wheelchairs and beds to ping pong tables and a shuffleboard court. After exploring the first building we headed down to the basement to see if the buildings were connected with underground steam tunnels, like many big institutions are. It was in the 90s outside, but as we descended the stairs the temperature dropped by 30 degrees and our flashlights wouldn’t go more than 20 feet in the fog from the extreme temperature difference. The air was heavy and it definitely got real creepy. The asbestos hanging down from rusted pipes didn’t worry us as much as what we might bump into. We did come across shrines with candles as well as graffiti, but no ghosts. The other buildings contained the employee cafeteria, operating rooms, pharmacy, and dentist office. Old medical equipment as well as typewriters and dictation machines were scattered about.

From forms scattered around you could see the place had been abandoned since the mid-1970s. We spent the day wandering around the abandoned wards. While mostly empty, there were still traces of life there, from wheelchairs and beds to ping pong tables and a shuffleboard court. After exploring the first building we headed down to the basement to see if the buildings were connected with underground steam tunnels, like many big institutions are. It was in the 90s outside, but as we descended the stairs the temperature dropped by 30 degrees and our flashlights wouldn’t go more than 20 feet in the fog from the extreme temperature difference. The air was heavy and it definitely got real creepy. The asbestos hanging down from rusted pipes didn’t worry us as much as what we might bump into. We did come across shrines with candles as well as graffiti, but no ghosts. The other buildings contained the employee cafeteria, operating rooms, pharmacy, and dentist office. Old medical equipment as well as typewriters and dictation machines were scattered about.

When did you make the connection to Woody Guthrie?

That night I went onto the Internet to do a search on Greystone to learn more of its history. One thing I discovered was that Woody Guthrie was there. I knew Guthrie’s role in folk music and knew some of his songs from growing up, but I wasn’t all that familiar with his story or music. From the movie Alice’s Restaurant I did remember that Woody died in a hospital of some rare disease. I kept wondering if Guthrie’s mug shots were somewhere in those files, but since they only had case numbers, his would be pretty much impossible to find. After going back to photograph Greystone a few more times by myself and doing more research on the web, I came across a site for the Woody Guthrie Archives and Foundation, which is located in New York (www.woodyguthrie.org) and a list of material they had relating to Guthrie’s years at Greystone, including some medical records. I also learned how Woody was suffering from Huntington’s Disease, an inherited disease of the nervous system, which destroys mental and physical abilities and is incurable. I also learned that a then 19-year old Bob Dylan traveled to Greystone in 1961 to meet his idol.

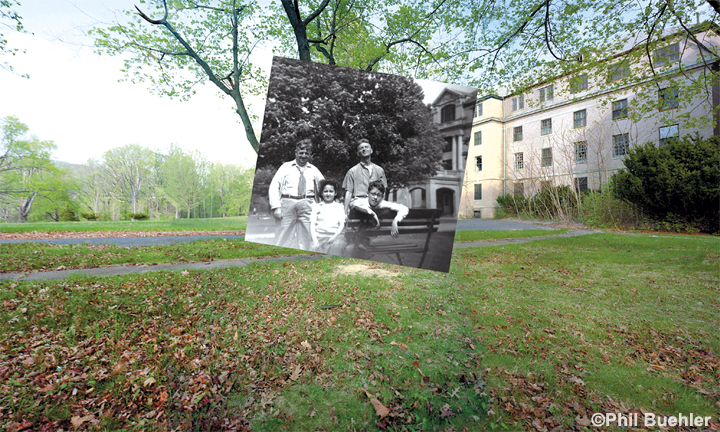

At the Woody Guthrie archives I met Nora Guthrie, Woody’s daughter, who recalled for me her visits to her dad when she was a kid and playing in the “magicky trees,” two huge weeping beeches, with her brothers Arlo and Joady. I read transcripts of the doctor’s exam given to Woody when he was admitted and learned he had been misdiagnosed as paranoid schizophrenic. Not much was known about Huntington’s back then, so Woody’s involuntary movements from Huntington’s were thought to be caused by other things. Looking through Woody’s medical records (while wearing those official white cotton archivist gloves) I came across what I was looking for–Woody’s case number–65935. I wondered if the mug shots would still be there forty years later?

I headed back to Greystone that week. All the files were in numerical order so it would be pretty easy to find the right envelope if it was still there. And it was, right there in envelope #65935. I felt like I was opening Tutankhamen’s tomb, finding something valuable long buried in a ruin. In his 1956 admittance photo, Woody was that charismatic riding-the-rails character we remember. In the discharge photo, when he was transferred in 1961 to Brooklyn State to be closer to his family, he’d lost a lot of weight and looked 25 years older. I met with Nora the following week and I surprised her and gave the negatives for the archives.

So where did the idea for a book about Woody Guthrie and Greystone Park come from?

I continued to photograph Greystone and do research at the archives for another year. I had gone back to school for a Master of Fine Arts in photography at the School of Visual Arts and Wardy Forty became my thesis project. I finished it by incorporating video, photographs, artifacts, music, interviews and archival material.

Nora showed me photographs of her family in front of the buildings at Greystone and I went back and shot the exact same place and later stitched the 1959 images into the images shot in 2002. I also incorporated the photographs I’d found in the darkroom in a video. Using “morph” software I created a one minute video loop, starting with Woody’s image in 1956 and ending with his image from 1961. The change between the two images is so slow that unless you watch for 20 seconds you wouldn’t think anything was happening. People have told me that they discover the change after realizing their feelings about Woody have changed. Nora also let me work with old 8mm family movies of the trip out to Greystone from the family’s home in Brooklyn, ending with Woody and Arlo playing guitar on the lawn outside Woody’s building. I retraced the car ride and shot video of the trip today and show them side-by-side on an old movie screen. Woody’s second wife Marjorie would sometimes check Woody out for the day and bring him to the home of Gleason’s, a couple that lived near Greystone, where folk singers from New York, including Dylan, would come and play, letting Woody experience a bit of what he had started and was now really blossoming in New York.

Woody also wrote hundreds of letters from Greystone, and I spent many hours in the archives reading them. I read that a student nurse played Woody’s first record, Bound for Glory, over the hospital’s hi-fi, so I returned to Greystone to recover the speaker. In the exhibit, Bound for Glory plays out of the actual speaker it played through at Greystone.

Woody also wrote hundreds of letters from Greystone, and I spent many hours in the archives reading them. I read that a student nurse played Woody’s first record, Bound for Glory, over the hospital’s hi-fi, so I returned to Greystone to recover the speaker. In the exhibit, Bound for Glory plays out of the actual speaker it played through at Greystone.

Woody sometimes ran out of paper and would write on whatever he could, including the inside of book jackets as well as paper towels. For the exhibit, I hung the paper towel dispenser from Woody’s ward on the wall next to a photo of a letter on the paper towel, and invited people to take a new paper towel and write a letter of their own and pin it to the wall.

In the end what I tried to do was create an exhibit that would transcend the ugliness and sadness of Woody’s disease and commitment at Greystone and let people discover how he was still having an impact in the world, or, as he signed one letter, “I ain’t dead quite yet, Woody.”

1 thought on “Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital”